The era of Chuck Yeager ends

"Chuck" Yeager, the American pilot and US Air Force Brigadier General who first overcame the sound barrier, has passed away aged 97.

Born Charles Elwood Yeager in Myra, WV, on February 13, 1923, he enlisted into the Army Air Force aged only 18 in September 1941. He started out as an aircraft mechanic and initially, he did not meet the educational standards to be trained as a pilot. Moreover, he felt so sick during his "baptism of flight" that he vomited all he could. Not a promising start. Yet, less than three months after his enlistment, the US entered WWII and the standards for flying personnel were loosened, allowing him to enter flight training. He displayed a natural attitude for flying and a 20/20 eyesight, which made for a good aim: he could shoot a deer at 600 yds (550 mt) when he went hunting for food as a boy.

After the end of his pilot training, he was transferred to the 363rd FS operating out of RAF Station Leiston, England. The unit flew P-51D Mustang fighters, and Yeager's aircraft was called "Glamorous Glen III" after his girlfriend Glennis Dickhouse who he would later marry.

"Glamorous Glen III". Here in color, for modellers: https://callie-graphics.com/products/p-51-glamorous-glen-iii-graphics-set

On his eighth mission, on March 4, 1944, Yeager shot down his first German aircraft. However, he was shot down himself the next day. Jumping out by parachute, he was aided by members of the Maquis, the French Resistance. They helped him return home via neutral Spain, but not before he taught them to make hand grenades (!). He earned the Bronze Star for helping a fellow airman, "Pat" Patterson, who was suffering from hypotermia, cross the border. By May 1944, Yeager was back to England.

Despite a strict rule that banned "evadees" from being again operational over Europe (to avoid endangering his French helpers), Yeager and fellow pilot Fred Glover managed to talk Brigadier General "Ike" Eisenower into letting them fly again. This would let Yeager's career "take off", literally. On October 12, 1944, he became "Ace in a day", i.e. he managed to shoot down five enemy aircraft on a single mission. The first two "kills" were courtesy of a German pilot who saw Yeager's Mustang behind him, panicked and collided with his wingman. Both men parachuted.

In 1945, married and with a pregnant wife, he chose to be transferred to Wright Field, closer to home. His awards and number of flying hours made him eligible as a test pilot. He served in this capacity at Muroc (now Edwards) Army Air Field, where the development of the Bell X-1 was underway. As Bell's test pilot, Chalmers Goodlin (also a veteran of WWII) demanded extra pay, the USAAF picked Yeager to fly the X-1. Since this kind of flying was more dangerous than usual, Yeager was suggested to have "paid up insurance". For instance, the X-1 was not equipped with an ejection seat. If the aircraft was not sturdy enough to withstand supersonic speed it would break apart. But bailing out at that speed was impossible.

The sound barrier was finally broken by Yeager on October 14, 1947. Two days before, Yeager was thrown over by a horse and broke two ribs in the fall. He went to a doctor and asked him to tape his ribs. The next day, Yeager was still in pain and asked his friend Jack Ridley to give him a lever to help him seal the X-1's hatch, and Ridley fashioned one from a broom handle.

The X-1 broke the sound barrier and hit Mach 1 (1,225km/h; 767mph) at 45,000ft (13,700m). Yeager did not decide to fly in spite of his injury to "be a hero" or to "behave cool", but probably because he felt he was the pilot who knew the aircraft best. If he had reported sick, the supersonic attempt would be delayed and the Air Force would find someone else to fly the plane.

And now, some scientific explanation. For the sake of clarity and of science books, Mach 1, a.k.a. the sound barrier a.k.a. speed of sound is attained when an object (aircraft) travels at the same speed of sound waves in the fluid considered (i.e. air). This speed is 1238 Km/h (761 mph) at sea level.

Chuck Yeager's X-1 was named "Glamorous Glennis" after his wife, like all the aircraft he flew. He felt that his wife was his "lucky charm". Although Yeager had the habit to know every aircraft and its manual like the back of his hands, he felt that sometimes he got out of trouble thanks to sheer luck. Like when "inertia coupling" sent his X-1A into a roll-pitch-yaw combination. Yeager blacked out for some time due to the 8g acceleration, then recovered his senses, put the aircraft in a normal spin. Then, finally, he regained full control and landed safely.

He said: "To survive took everything I knew and had ever experienced in a cockpit, so that maybe one hour less flying time could have been the difference between drilling a hole or landing safely. I saved myself from sheer instinct based on hundreds of previous spin-tests. Experienced at spinning down to earth, I was less disoriented than others who had done it many fewer times, and was more likely to make the right moves to save myself.”

The data collected during these flights also helped develop the early space flight programmes. All this epic would later be narrated by author Tom Wolfe in his book "The right stuff". One might think that Yeager certainly had "the right stuff" to go into outer space, but ultimately the leaders of the Mercury Programme thought he was not suited since he had no higher education. Instead, all other astronauts he helped train had degrees in Engineering or other Science subjects besides being experienced test pilots.

Yeager served through three wars (WWII, Korea, Vietnam) and flew a huge variety of aircraft (around 150), even a North Korean MiG-15 which was brought over by a defector. "In the end, we knew more about the MiG-15 than the North Koreans did".

He also tested the NF-104, i.e. a Starfighter specifically modified with a rocket engine devised for stratospheric flight, to be used for astronaut training. That kind of aircraft had maneuverability problems, and went into a spin from which Yeager could not recover.

He jumped out at the last second, but the ejection seat tangled in the lines of his parachute. When it dislodged, the still-hot rocket smashed against the visor of his helmet and ignited the pure oxygen still contained in the space suit he was wearing. He landed with his parachute alive, but with third-degree burns. The blood flowing from a cut above his left eyebrow solidified in the fire and probably saved the left eye.

The incident was narrated in Tom Wolfe's book "The Right Stuff" on which director Philip Kaufman based his movie of the same name. Kaufman altered and highly romanticized Yeager's life and the facts related to the Mercury programme; Tom Wolfe made it clear that he did not like the movie. Moreover, the aircraft used in the movie scene was a standard F-104 with no rocket booster. Some years ago, the Air Force released actual footage of that flight. At least it does some justice to the facts.

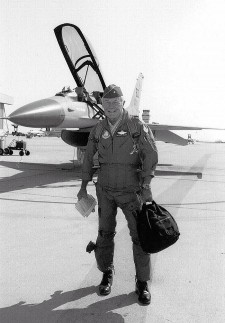

Of course he was back in flight after convalescence, and his retirement after 33 years of service was only a formality: as a matter of fact he would sit at the controls of an aircraft again until very late. Not only sports aircraft, but F-15s, F-16s and a P-51 that the Air Force gifted him.

Further reading:

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chuck_Yeager

https://www.airspacemag.com/history-of-flight/sky-high-3270307/?page=1

https://www.f-16.net/interviews_article35.html

https://www.artofmanliness.com/articles/lessons-in-manliness-chuck-yeager/